Planning is not guessing, Planning is training

What planning is and how to do it properly has been driven by our need to manage time. But that’s not what planning is all about. Time is not something we can manage; time is something we spend. Planning helps us decide how we spend time. But first, we need to understand what planning is.

There is a famous planning law that almost everyone knows and follows instinctively. It was first articulated by Douglass Hofstader, an American physics researcher. Named Hofstrader’s Law, it goes like this:

It always takes longer than you expect, even when you take into account Hofstadter’s Law.

The simplicity of this law and its almost universal adherence is mindboggling. Nowhere does it apply more than in planning.

People are terrible at planning. We’ve spent years trying to organize ourselves and our work. But so far, we have not managed to get better at it. We’ve been pretty good at planning simple tasks and work processes. But with each increase in complexity, even the most intelligent of us can never plan something accurately.

Why does this happen?

Mostly because planning is guessing, planning is our attempt at projecting the present into the future. And no one really knows the future. Unforeseen events or poorly understood outcomes can dramatically change even the best-designed plans. Furthermore, the complexity of our work can significantly alter the completion timelines and change the probability of a successful outcome. We could be following a plan that is doomed to fail.

The problem with how we understand planning.

What happens when we create plans? We guess as to what is going to happen in the future.

A long-term life plan of going to college, then graduate school, followed by a prestigious research position at a famous university, can be delayed or derailed by personal circumstances or national-size events.

A complex business plan that projects ever-increasing revenues years into the future can be made obsolete by introducing a new value delivery method. Think Blockbuster and Netflix. Blockbuster’s dominance was derailed by Netflix easy to use streaming service.

But the biggest culprit in derailing our plans is time. We need to know how long each task will take because time is truly the only commodity we can’t make more. So estimating how long something will take to complete is of utmost importance.

The sooner we get our current task finished, the quicker we’ll be able to start doing something else.

And when it comes to estimating time, the same effects that usually derail task completion success also derail our time estimates. There are too many unknowns, and we don’t know the future.

When we plan, we tend to assume that everything will go according to plan. Because of this, we almost always tend to underestimate the likelihood of things going wrong and negatively impacting our plan. And even though we plan for contingencies, we rarely add things like “global virus pandemic” or “national debt crisis” to the list of possible disruptors. Even rarer do we think about someone falling sick and causing a delay in the project?

Our inability to tell the future means that people have a persistent tendency to underestimate how long something will take to complete. The complexity of the task or a project decreases our ability to provide accurate time estimates.

On complex projects with high interdependencies, the likelihood of something going wrong is almost 100%. Almost.

One of the reasons for this is because most plans drastically underestimate the amount of extra time needed to make the plan more accurate. Project managers often add some extra time to the completion of the project. This slack time usually includes things like expected delays, vacations, and unknown unknowns.

It’d be best to double the time estimates on short projects and tripled or quadrupled estimates on more complex projects. But that’s almost always impossible.

Including significant slack time or doubling time estimates is rarely seen as acceptable. If you go to your boss or your customer with a plan that involves 6 months of padded time, just in case, the most common answer to that query is, “not going to work, and we need it done faster.” You have no choice but to shorten the time to please your boss or customer. Even though you know what the result will be.

However, having this cynical view of planning and time estimation shouldn’t stop you from actually making plans. We have been fooled into thinking that plans use useful because they help you predict future success.

That is rather a minimal and, frankly, a naive understanding of what plans are for.

Plans are useful because they help you understand what is involved in achieving future success. In other words, plans are not about timing things perfecting. Plans are about making you aware of the scope of work that’s involved.

Planning helps you understand requirements, dependencies, and risks more completely and thoroughly.

Without a Plan

What happens when you don’t plan and do what you think you need to be done at that moment in time. You get things done, of course. Slowly, task by task, step by step.

Then bam! You get stumped. An answer from the supplier comes in, and they don’t carry that part number anymore. Your boss responds with a harsh NO to your request for more resources. What you thought customers wanted is completely wrong. They don’t want something completely different.

Things like that happen all the time. But if you are not used to planning, you soldier on, going from fire to fire, putting them out as best you can. After each workday, you end on your couch, exhausted, unmotivated to do anything and depressed.

When people ask you to do things, you always say no because you have no time. And that is a very true answer. You have no time to spend on anything else.

Why Planning is so Helpful

The value of a good plan is in the process of planning. Sure there is tremendous value in executing work according to plan. But, nothing beats the planning process.

What do you do when you plan? You perform a mental simulation of what should, could, would happen at every step of the plan.

You are building a map and plotting a route at the same time, in your mind.

More often than not, you begin planning by constructing a map. You know where you want to go and roughly when you want to get there. The unknown is the area between you and your destination.

So you spend some time learning about the area, maybe looking for other maps. What if someone else already explored the area and mapped out the terrain? If that is the case, you are ahead. If not, you have to do it yourself.

Once you have an idea of the terrain and your map is done, you begin to plan a route. Some waypoints will be useful, and there places on the map that you know you should avoid. So you carefully plan the path to your destination.

And that is why planning is so helpful. It’s a mental exercise that helps you figure out how to get from point A to point B.

Two Types of Maps

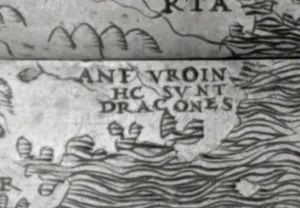

There are two types of maps that you should be aware of. The first is similar to the map of unexplored land. The “Here Be Dragons” type of map.

The map where most of the territory is unknown or unexplored is common in the software development world. Whenever developers build a new piece of software, they have no idea what it will look like in the end or what problems they will encounter.

Similarly, research-type projects are in the same category. Discovering a new vaccine, tracing the origins of the virus or even distributing vaccines to the whole world is part of the “Here Be Dragons” type map.

When faced with this situation, you will have to be careful when creating a route to your destination. There are just too many unknowns. It is best to create short plans as you explore terrain one small chunk at a time. And it is important to be able to pivot, change direction or retreat if the situation calls for it.

There is a popular methodology for planning in the “Here Be Dragons” type terrain in the software world. It’s called Agile Methodology. The primary premise is to plan 1 or two weeks in advance and continually check if you are going in the right direction.

This methodology can be applied to other fields, not all, but many.

The second type of map is more like a Google Map.

This is an easy map to follow. Someone has mapped all the routes, has tried all of the roads, and all you have to do to get from point A to point B is to pick a route and go.

In planning, this type of map is often found in repetitive processes. For example, when building new car models, the steps are almost always the same. Design, Prototype, Engineer, Manufacture, Test, Sell. Of course, this is an oversimplification, but overall, that’s how it is usually done. We’ve built so many cars that we know what needs to be done.

Note: Building an electric car is different. Because planning that process is in the “Here Be Dragons” territory.

Other industries fall into the “Google Map” type planning processes. Most of the steps are known, and mostly external factors affect how long the result takes to achieve.

When planning, figure out the map type.

When planning, it is important to know when map type you are on first. Are you planning something that’s never been done before? If so, you are on the “Here Be Dragons” map, and you have to explore terrain first.

If you are planning something that’s been done several times, albeit a little bit differently every time, then you are on the “Google Map” planning process. You can pick a route, and eventually, you’ll arrive at your destination. You might be delayed by traffic, roadwork or a longer than expected lunch stop.

Planning is not guessing. Planning is training.

When elite athletes train, they do many physical movements, tactical exercises, individual strengthening and real-world scenarios. For example, a typical weekly training process for elite soccer players consists of physical training sessions, ball work, individual skills practice, tactical games, gameplay review and development, tactics lessons, opposition play review, and much more. And all of these activities help these players become very good at what they do.

But there is also another exercise that is now commonplace among elite athletes. This exercise is all about imagining yourself in a particular situation and mentally going through the steps and actions you need to succeed. For example, strikers often go through the mental exercise of receiving a ball from midfield, turning with the ball, pushing the ball to the left, looking up to see where the keeper is and taking a shot.

This is how they create a plan of action for this particular situation, and they rehearse it on the field and in their mind.

In real-life situations, on the field, things like that really happened according to the plan. It’s always different, but an athlete’s brain has done enough iterations, enough planning that it knows how to react. It puts together a slightly different plan and executes.

This is what planning is for. It is a form of training to help you prepare for real-world situations. It helps you understand possible steps you need to take and how to react should the need arises.

So remember. Planning is not guessing. Planning is training.